What’s in store for the economy in 2022? Omicron is on everyone’s mind now and coughs, colds, sore throats and fevers are everywhere among the vaccinated and unvaccinated. That feeling of tiredness may not necessarily be due to COVID-19 though.

It could be the Duterte administration’s underwhelming response for two years now that’s getting tiresome. The government can do so much more than its emerging twin-pronged strategy of downplaying the pandemic – including hiding its true impact from the public – and putting the burden of adjusting to it on the people.

Reopened

The biggest thing the economy had going for it coming into 2022 was reopening after the protracted and periodic lockdowns since the coronavirus first hit the country. Key indicators such as Google mobility data clearly show increased activity especially since September 2021 and through the holiday season, also corresponding to lower COVID-19 response stringency index measures since the middle of the year.

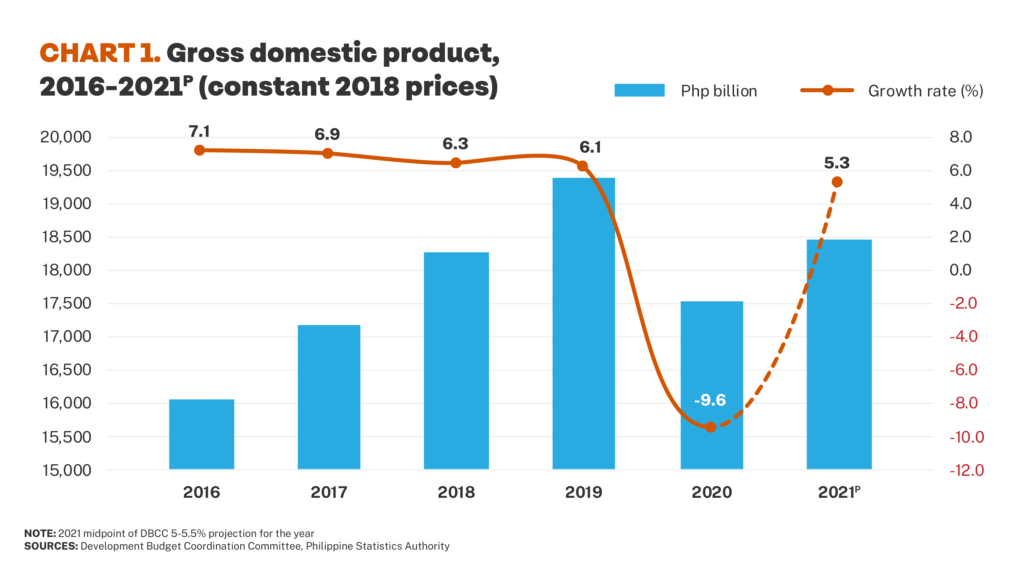

Despite this reopening, it is however conspicuous that the economic rebound has still been very shallow. It looks like gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2021 will still just make up for barely half of the -9.6% growth (contraction) due to the lockdowns in 2020. (See Chart 1)

This is most of all due to the economic managers putting more emphasis on so-called fiscal consolidation than the fiscal stimulus so needed by the lockdown-ravaged economy. National government budget increases in 2020 (11.3% increase) and 2021 (9.9%) were actually even below the 14.3% average increase in the period 2016-2019. The 11.5% increase in the recently approved 2022 budget is also still below par.

So while there’s some momentum from reopening, the economy is still weighed down in 2022 by the effect of government conservatism and stinginess. It still isn’t doing enough to fix the damage its lockdowns caused on aggregate demand and supply.

Dampened

Household consumption accounts for some 70% of the economy. The loss of incomes and livelihoods is however huge and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) reports that around seven out of ten (69.8%) households didn’t have any savings as of the fourth quarter of last year. This is consistent with a Social Weather Stations (SWS) self-rated poverty survey in September that had 79% of families reporting themselves as poor (45%) or borderline poor (34%).

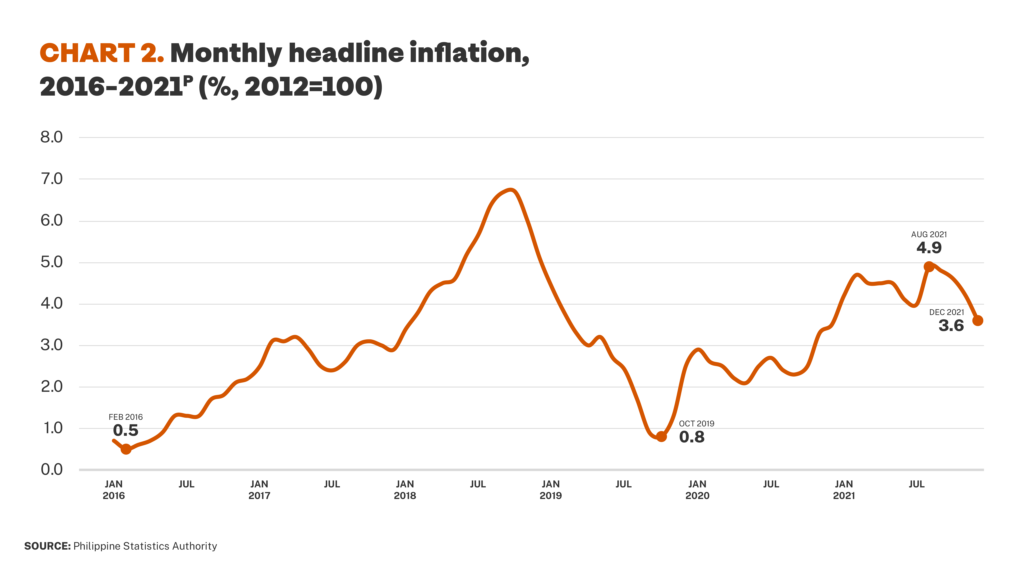

Implicitly low incomes are eroded further by how inflation has been mostly accelerating since the end of 2019 or even before the pandemic. (See Chart 2) These are huge dampeners on aggregate demand aside from indicating considerable distress to poor families and household welfare.

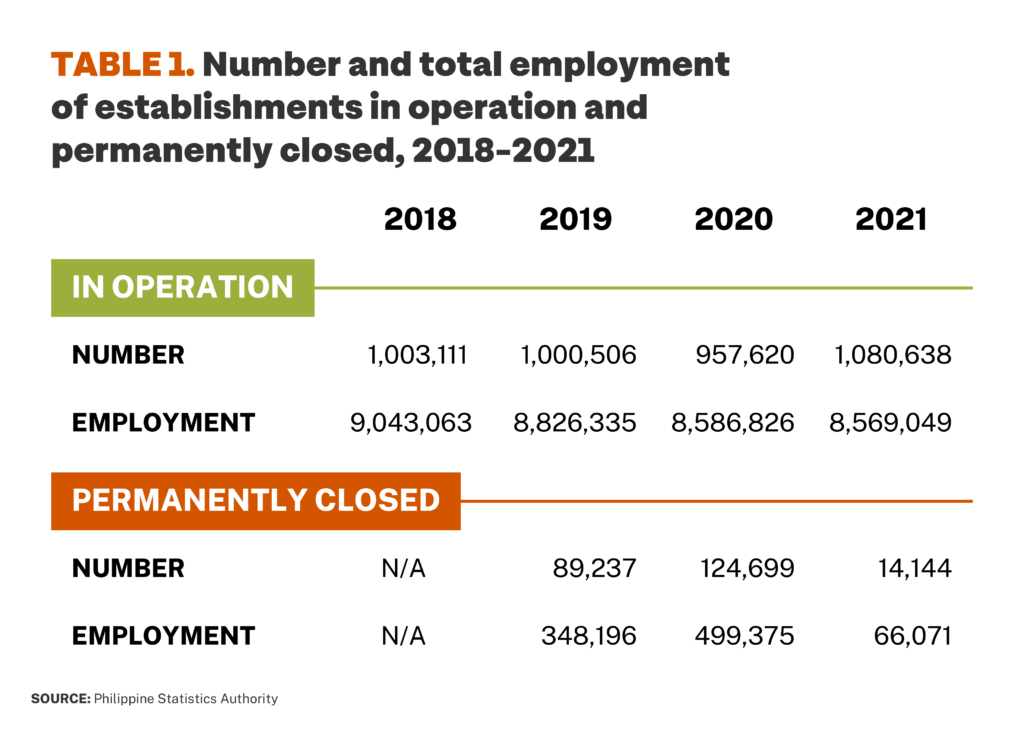

On the supply side, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported 138,843 establishments employing 565,446 people permanently closing in 2020 and 2021. (See Table 1) This however does not count likely tens of thousands more informal unregistered establishments that closed but were not captured by official statistics.

December labor force figures still aren’t out but these will likely only confirm that 2022 is starting with high unemployment and greatly worsened quality of work. These repress consumption spending and, by extension, enterprise growth. They are difficult conditions for smaller establishments to reopen, expand or even just stay in business. Telecommunications, energy, water, banking and finance, and real estate and construction where tycoons concentrate are the only ones recovering quickly and looking to thrive.

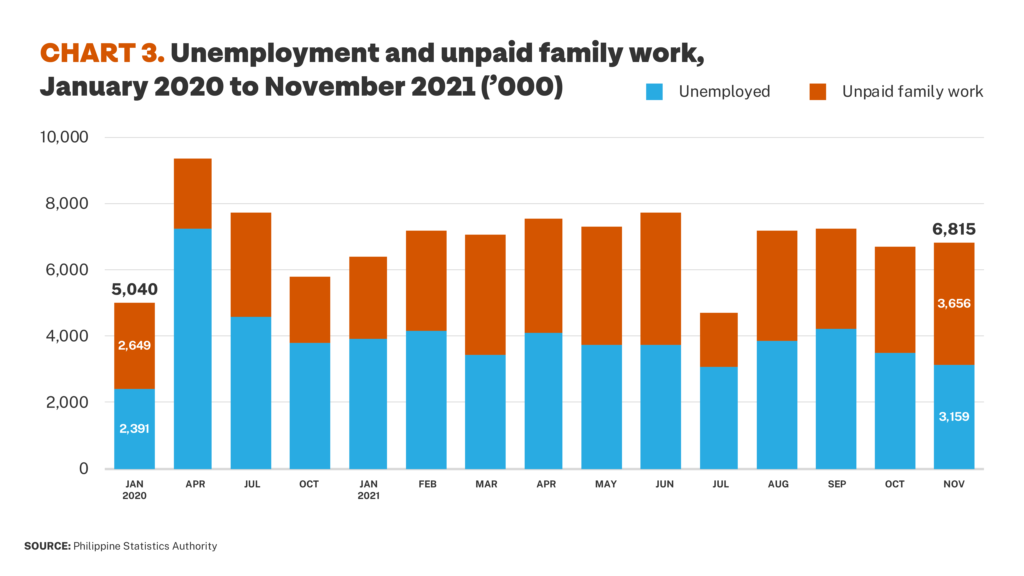

Unemployment is officially reported at 3.2 million as of November 2021. But it may be as much as 8.3 million if unpaid family workers (3.7 million) and uncounted jobless merely because of a stricter definition of unemployment since 2005 (some 1.5 million) are also counted. Unemployment and unpaid work have remained stubbornly high despite the economy reopening. (See Chart 3)

Reported increases in employment unfortunately do not really reflect stable or decent-paying work. The 2.9 million net employment created by November 2021 compared to pre-pandemic January 2020 is wholly informal in irregular self-employment (1.5 million) and unpaid family work (1 million). It should moreover be noted that there are 389,000 less full-time workers and 457,000 less wage and salary workers in private establishments.

Slowing world

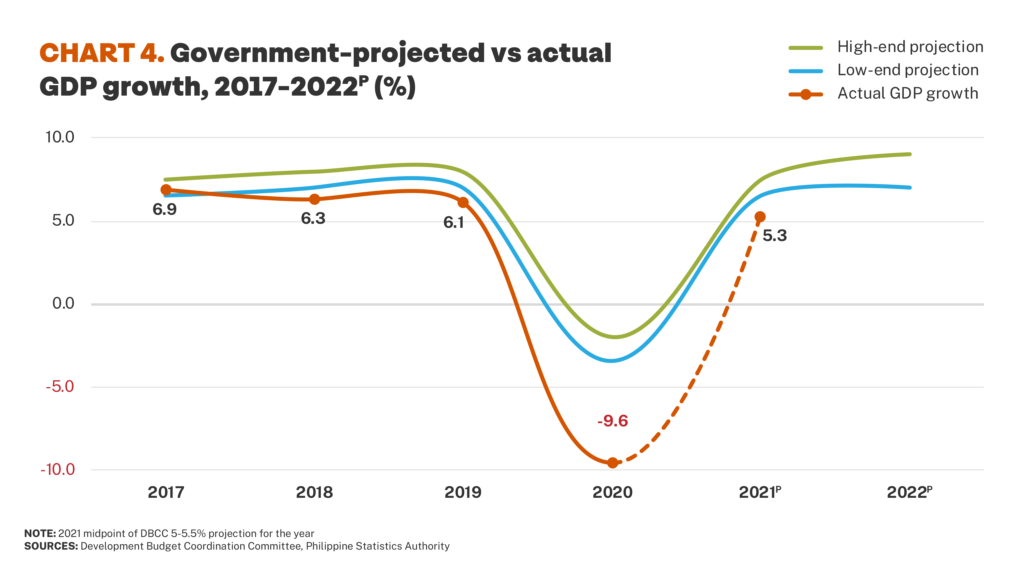

The government target of 7-9% growth in 2022 is questionable – the economic managers have never met their declared original growth targets since 2017, and just revise targets as actual adverse performance becomes evident. (See Chart 4) The so-called growth momentum is mainly imagined.

The effects of reopening are overemphasized and the impact of economic scarring underestimated. It also remains hazy if the pandemic really is on the way out in the country or abroad. The impact of new variants like Omicron and others that are different in terms of transmissibility, severity and resistance to vaccines remains to be seen.

And it’s not as if all is well in the world economy. It may seem a long time ago but when the pandemic hit in 2020, global capitalism was into 11 years of striving, and failing, to overcome protracted stagnation since the 2008 global financial and economic crisis. As in the Philippines, rebounding back to this only seems desirable because of how bad things were when the world locked down.

Today, there is still that protracted stagnation to deal with but also a number of additional stressors. Foremost is vastly higher global debt which hit a record US$296 trillion, equivalent to 353% of global GDP, by the middle of 2021. Monetary policy will likely tighten soon to rein in high inflation. Rising interest rates will cause tremors in the debt pile including in the Philippines.

But global unemployment is also higher and supply chains are possibly in flux. Global growth will almost certainly decelerate in 2022 and beyond especially as fiscal stimulus in other countries fade – real stimulus, unlike the press release version in the Philippines. The United States (US) and China are the acknowledged biggest drivers of the global economy; they are each already hitting their respective rough spots aside from still bickering with each other.

Slowing PH

Domestically, the base effect driving the country’s GDP growth last year will start tapering off in the first quarter of 2022. With the rebound from reopening over and weighed down by lockdown-induced economic scarring, the economy is unlikely to return anytime soon to even just its pre-pandemic growth rates.

The pre-pandemic trajectory is perhaps also not even something to want to return to. Economic growth was slowing for three consecutive years even before the pandemic from 7.1% in 2016 to 6.9% (2017), 6.3% (2018), and 6.1% (2019). (See Chart 1) Despite much administration hype, the economy was not really developing any long-term growth drivers.

Lacking fresh ideas, the government is also putting too much faith in its stale Build, Build, Build infrastructure program to revive the economy. As the Duterte administration’s economic managers do not tire of telling, the public infrastructure budget has been continuously rising under its watch. It almost doubled (78% increase) from Php590 billion in 2016 to Php1.1 trillion in 2019, with the equivalent share in GDP increasing from 3.9% to 5.4% over that time.

Yet over 2017-2019, economic growth still kept slowing and annual average job creation of 313,338 was the slowest in 35 years or among all post-Marcos administrations. The gains were disproportionately low even in construction subsector employment. Between 2016 and 2019, this only saw a 23% increase to 4.2 million mainly low-paying and short-term jobs.

Election spending this year may also not give the accustomed boost many may be hoping for. The more unresolved the pandemic and the less physical campaign-related activities, then the weaker the additional impulse.

As it is, the best-case scenario with the government’s business-as-usual approach is that the country ends 2022 at around its pre-pandemic 2019 level of economic output. This means that three years of economic growth will still have been lost, not to mention the immeasurable suffering and hunger over that time of tens of millions of poor and low-income families.

There will be growth in 2022 – this is inevitable with the reopened economy – but it will not be broad-based. Nor will it fix worsening job scarcity.

Recovering

Which is not to say that all this has to be a foregone conclusion. If it chose to, the administration that is exiting and the new one entering can take a more rational and humane approach to recovering and reforming the economy.

This starts with breaking the inertia of tepid public health measures to contain the pandemic. Mass testing, diligent contact tracing, and smart quarantines that do not burden the working class remain the ideal measures to avert explosive case numbers and the uncertainty and distress in their wake. The Omicron variant has shown how over-relying on vaccinations is insufficient when new variants can still arise because global vaccination is still so uneven and lacking especially in the global South.

Giving meaningful cash assistance to the poorest 18 million families will not just improve their welfare but also spur consumption spending and aggregate demand. The hundreds of billions put in their pockets to spend will also be a much more effective fiscal stimulus than the same amount going to capital-intensive or import-dependent or corruption-wracked infrastructure projects.

This does not have to be inflationary. Likewise giving meaningful support to domestic agriculture and local enterprises can ensure a supply response. This support can also be given with a long view to expanding rural productivity and spurring Filipino industrialization. These are still the essential foundations of the national economy, job creation, and dynamic modernization.

The fiscal constraint need not be binding. Large government deficits and, to some degree, even rising debt can be justified if these result in increased economic activity. The problem is not large deficits and debt per se – rather, it’s why we cannot more quickly grow out of these deficits and debt in a way that lifts the conditions of the majority instead of just a few.

Radicals

The economic managers also favor credit ratings, competitiveness, openness to foreign investments, international reserves, and other such indicators. This however confuses what are merely possible means to development as ends in themselves. In the worst instances – such as with regressive tax “reforms” – outright anti-development measures are portrayed as steps forward.

The result is paying scant attention to real economic foundations, decent work, and eradicating poverty for the majority – while over-emphasizing profitability for conglomerates and the wealthy families owning them.

The pandemic has been a radical shock to the country. Entering the new year and, soon, a new administration, it is also timely to ask for more radical measures breaking from the economic conservatism which has weighed down the economy and development for the people for so long. ###